Last year, I published a poetry collection that includes the following poem:

Sitting Backward on the Bus

Most claim the front-facing seats

but I opt

for the rear

to watch what is

become what was

rather than imagine

what may or may not be.

What was

is what is

still to come.

And it never lies.

Which is why

I visit the past

perhaps one of the last

looking backward

moving forward.

Indeed, “What was is what is,” though it is no longer “still to come.” The tragedies of my people’s past have become the realities of its present. One need not look backward anymore.

---

I grew up in suburban New Jersey in the 1970s, carefree of the hate and terror my parents barely survived in Europe during World War II. I shrugged off, even laughed at, their periodic warnings that such things could happen again. My one brush with American antisemitism came years later, during a job interview in smalltown Indiana, when a potential employer asked me if I “wouldn’t feel more comfortable living in New York.” A coded message, for sure, but not one that was terribly harmful, I figured.

When I moved to Israel in 1999, it was not in search of a safe haven from antisemitism. I viewed Israel as the place where the Jewish future was unfolding. I wanted to be part of it; I wanted my children to grow up in it. Israel may have been the Jews’ ancient homeland, the object of the Jewish people’s yearning for millennia, the fulfilment of a biblical promise. But equally important, it was the cradle of Jewish hope. In ways the Star-Spangled Banner’s “bombs bursting in air” never spoke to me, Israel’s national anthem, “HaTikvah” (The Hope), said it all.

I have always refused to view incidents of antisemitism as remnant sparks from the Holocaust. No, those embers had been extinguished for good, I believed. Jew-hatred on such a scale could never be reignited. Antizionism need not be equated with antisemitism.

How wrong I was.

Hamas’ barbaric attack on October 7, 2023, was yet another version of the age-old pogrom, with the added twist of hostage-taking (239 by today’s count) to make impossible an Israeli victory in the war that would inevitably follow. Then came the protesters in world capitals calling for a Palestine “free from the river to the sea,” and an end to Israel’s “occupation” (i.e., its existence). This week, Cornell University students put out a call to “follow Jews on campus and slit their throats,” and a mob stormed a Russian airport to attack Israeli arrivals. Antisemitism, it turns out, remains combustible. The Jewish world is on fire.

And so, I tell myself, I must redefine my relationship with my country. As difficult as it is to accept, I must narrow my view of Israel to be my—our—only safe haven. Israel can remain the path to the Jewish future, as long as it can protect us in the terrible present.

But what if it can’t? Since the Hamas attack, I’ve watched the heavy mantle of “safe haven” slip down Israel’s formerly proud shoulders. In my 25 years living here—years punctuated by suicide bombings, car rammings, and knife attacks—I have never felt more vulnerable, more unsafe, than during these last few, terrifying weeks.

---

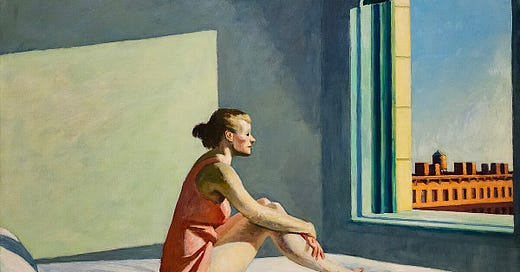

At the launch party for my poetry collection, the evening’s host, a visual artist, remarked that my poems’ expressions of aloneness reminded her of the work of Edward Hopper. I replied that there is something else in Hopper’s paintings which I have always found remarkable: their sense of suspended time. Hopper’s images of stark diners and gloomy hotel rooms seem to capture moments between other moments. When you look at them, you can’t help but wonder, “What happened just a moment ago to thrust this person into this hopeless scene?” and “What will happen to her next?”

Those are the questions I am asking myself now.

Your post really good, so thanks! And as to "Edward Hopper" both in general and as to the painting illustrating your post: In approximately 1983 my husband and I went to a convention-- in Chicago-- in his then industry. While he was at meetings, I took myself off to the Art Museum that had a Hopper exhibition. I walked out of there crying and reacting as if I had had a religious experience. Prior to the exhibition I had only seen Hopper work on paper, including in a maybe 9 x 12 paperback devoted just to him. I cannot urge strongly enough to do anything you and all that like him can to see his original work: you NEVER saw such light poring out of canvas! You just can't imagine what a profound experience.